Students whose instructors regularly visit the Faculty Engagement Center achieve statistically significantly higher quiz scores than students whose instructors do not.

Instructors play the primary role in improving student success. You decide how in-class time is used, what kinds of activities and assessments students will engage with, which educational materials students will use, and make dozens of other choices to support student learning every term. But how do you get the support you need to improve student success?

Example of a presentation slide with an active learning prompt from the Lumen One Introductory Statistics course.

For example, you’ve probably heard that using active learning in class will increase student learning. But you also know that preparing those activities takes a lot of time, and so you may have (rationally) decided to put off using active learning in your class again this term.

Here’s some good news! The comprehensive support resources in Lumen One’s Faculty Engagement Center make using active learning simple and easy. These resources include fully prepared active learning activities for each week, including an instructor guide you can review quickly to get ready to lead the activity and slides you can use in class to guide your students.

The Faculty Engagement Center includes many other time-saving tools that can help you improve student success.

For example, a real-time view of students’ understanding of the week’s topics lets you decide, at a glance, which topics you should spend more time on during class and which you might not need to address as deeply. Additionally, the Get to Know Your Students tool helps you quickly access students’ preferred names and majors, their class activity, and other relevant information that will make office hours visits more powerful – and more efficient. And messaging tools make it easy to send notes to students congratulating them for excellent work, send study tips, or invite them to office hours when they’re struggling.

The Faculty Engagement Center in Lumen One makes it simple and easy to use more evidence-based teaching practices in your teaching. A review of Fall 2023 data shows that students whose faculty access the Faculty Engagement Center at least twice a week achieve quiz scores two points higher on average than students whose faculty visit the Faculty Engagement Center monthly or less often.

Lumen is deeply committed to eliminating race, income, and gender as predictors of student success in US higher education. Each and every student, regardless of their race, income, or gender, is capable of succeeding when they are supported effectively. And at Lumen, we are working to provide every student and each instructor with the pedagogical supports they need to be successful.

In 2022, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation provided Lumen with substantial funding in support of this vision. This generous grant allowed Lumen to update and improve our equity-centered design process, leading to significant improvements to our content and assessments as well as a new software platform for supporting students and instructors as they engage in the teaching and learning process. The new courseware offering that resulted from this work is called Lumen One, and the first subject is Introductory Statistics.

Equity-Centered Design

We define equity-centered design as “the practice of purposefully involving historically marginalized and resilient communities throughout a design process with the goal of allowing their voice to directly affect how the solution will address the inequity at hand” following Kwak (2020). This principle is sometimes expressed as “design with, not for.” As we created Lumen One, we involved students and faculty throughout the process of drafting platform features, content designs, and assessment approaches.

One of our key strategies for designing with students, instead of for them, was the creation of two User Testing Centers (UTCs). Through partnerships with Santa Ana College and Rockland Community College, two Minority Serving Institutions, the UTCs trained 13 student interns to complete user testing research cycles with more than 140 of their student peers. Using a variety of research techniques – from empathy interviews and cognitive interviews to prototype testing and interactive co-design sessions, the interns helped Lumen understand the answers to questions like: What’s the reality of students’ lives and academic experiences today? How might students solve the problems they experience in their gateway courses? What’s interesting, relevant, and engaging to them? What definitely isn’t? What would students change if they could?

Examples of Equity-Centered Designs

Students taught us many valuable lessons through their work with the UTCs. One of those lessons is that there’s nothing that students find universally interesting and relevant to their lives. This recognition led us to co-design data analysis practice in Introductory Statistics that has a greater chance of engaging students by including multiple datasets. This gives each student a chance to choose a topic to analyze that’s meaningful to them. We call these Choose Your Own Dataset activities.

Students also told us that they frequently need to hear a concept explained multiple times by multiple people. This typically leads them to search YouTube for additional perspectives on challenging topics. However, surfing YouTube presents a number of challenges. Different instructors use different language to describe the same concepts, making them more difficult to understand. And the YouTube algorithm always suggests unrelated videos that easily distract students and waste their time. Understanding the underlying desire for additional perspectives as well as the challenges presented by using YouTube for this purpose, we recorded three different instructors with different perspectives and life experiences explaining key concepts throughout the course. This allows students to get a range of perspectives on challenging ideas without the confusion and distractions of YouTube.

In another example, students told us they strongly wish that instructors better understood them as individuals and appreciated the obligations they have outside of class, like working full-time or caring for an aging family member. Many students long to feel a genuine connection to their instructors and to feel seen and supported. To help bridge this gap between instructors and students we co-designed an Introduce Yourself activity for students and a corresponding instructor dashboard. This provides faculty with information like students’ preferred names and pronunciation, preferred pronouns, academic majors, year in school, and obligations outside of class.

As a final example, we heard loud and clear from students that they don’t enjoy reading long monolithic blocks of text. This complaint actually aligns very well with research about what makes for effective studying. Specifically, research consistently shows that engaging in interactive practice with immediate feedback is dramatically more effective at promoting learning than reading or watching video.

(And this effect of doing interactive practice is causal, not merely correlational.) This student perspective combined nicely with another consistent bit of feedback– that students hate having to purchase a calculator or special mathematics software in order to do homework for their classes. We brought these ideas together in a co-design that significantly reduces the amount of passive reading and video watching that students do in the course. In place of reading and watching, students engage in significantly more interactive practice, including with an online statistics tool that is integrated directly into the course materials at no additional cost.

Equity isn’t Just a Process – It’s Also Results

It’s often said that equity is a process, and I agree with the call to action underlying that idea. But equity must also be about results. For example, if Lumen’s equity-centered design process doesn’t facilitate equitable outcomes for students, then our process still needs work. We recognize that there are likely many cycles of continuous improvement between us and the audacious goal of eliminating race, income, and gender as predictors of student success. With Lumen One Introductory Statistics available for broad adoption this fall, we’re excited to evaluate our initial progress towards this goal, publicly share what we’re learning, and continuously re-design Lumen One with – not for – students and faculty across the US in pursuit of equitable outcomes.

Interested in Learning More?

Hear what your peers who’ve adopted Lumen One have to say during a webinar on October 26th at 2:00 p.m. ET.

Register here: https://info.lumenlearning.com/exploring-lumen-one-in-the-classroom

References

Kwak, J. (2020). How equity-centered design supports anti-racism in the classroom. https://www.everylearnereverywhere.org/blog/how-equity-centered-design-supports-anti-racism-in-the-classroom/

The post Exploring Lumen One: A Deeper Look at the First Equity-Centered Courseware first appeared on Lumen Learning.]]>

Last month, I participated in a panel at SXSW EDU, titled “Equity-Centered Research for Innovative Courseware” where I was joined by moderator, Felice Nudelman, Associate Vice President of Academic Innovation and Transformation at AASCU, and fellow panelists Ángel López, Design Director at Blink UX and SL (Shree Lakshmi) Rao, Research + Strategy Director at Substantial. The conversation served to provide different perspectives on this topic – representing research, design, and product implementation – and discuss how technology companies can use equity-centered research and design to reimagine equitable student success.

For those seeking to design courseware with equity in mind, here are some of my key takeaways from the panel:

- Building compassion and awareness into your team is essential. Designing courseware with equity at its core can be challenging from an interpersonal perspective, as it demands a considerable amount of grace and empathy. Building a team of individuals who can interrogate their own personal biases, interrogate what they are bringing to the design process, and embrace centering the historically marginalized user experience will ultimately set up organizations for success.

- This process requires co-creation and continuous improvement. Those that engage in leveraging equity-centered research and design should be aware that it is a very iterative and collaborative process. Using this approach, the idea is to consistently test and iterate based on student feedback in real-time. It is also important to engage in co-creation and work with students, rather than for them, especially those representing diverse populations. When students have the freedom to share their perspective of what works and what is effective, the result can produce highly impactful input to a product’s development.

- Integrating equity-centered research and design into courseware doesn’t happen quickly. The principles of equity-centered design call for taking the time in the development process instead of moving quickly to build a product. This time allows for those involved to be very intentional with each step and understand the nuances of gathering information, especially when it comes to working with students directly. Team members should be mindful of student schedules and commitments, and acknowledge their time and contributions by compensating them appropriately.

If you’re interested in learning more, request a demo of Lumen One, the first courseware product built with a focus on equity.

The post Lumen Learning Participates in SXSW EDU Panel on Equity-Centered Research first appeared on Lumen Learning.]]>Dr. David Wiley | Founder & Chief Academic Officer

Helping people adopt evidence-based practices is notoriously difficult. Even in matters of life and death, evidence-based practices frequently go unadopted or take an incredibly long time to enter widespread use. As Bauer, et al. (2015) explain,

It has been widely reported that evidence-based practices (EBPs) take on average 17 years to be incorporated into routine general practice in health care. Even this dismal estimate presents an unrealistically rosy projection, as only about half of EBPs ever reach widespread clinical usage.

Soicher, Becker-Blease, and Bostick (2020) describe a similar – perhaps even worse – state of affairs in education:

Despite the tremendous advances in basic and applied research in cognitive psychology, educational psychology, and the learning sciences, few evidence-based practices have been taken up by college professors into routine practice in college classrooms, while ineffective practices stubbornly remain.

Why is it so difficult for people to adopt evidence-based practices? In the case of college and university faculty adopting evidence-based teaching practices, the reasons appear to be personal. Smith and Herckis (2018) provide an amazing report of related work in the adoption of technology-enhanced learning resources, which has definitely influenced my thinking on this topic.

It’s a truism in higher education that the majority of faculty have advanced degrees in their disciplines but no formal training in teaching and learning. Absent formal training, many faculty replicate the teaching and learning practices of one (or more) of their favorite professors. Under the circumstances, this is a completely rational approach. If you took one or more classes from someone, learned a lot, and even went on to become faculty yourself, then your former teacher’s practices must have been effective. “I know they work, because they worked for me.”

Faculty’s mental models of what “good teaching” looks like are thus deeply personal because they are intertwined with their own experiences as learners. Their teaching practices can even become entangled with their sense of identity, leading faculty to think of the way they teach as a part of “who they are.”

Consequently, the invitation to adopt an evidence-based teaching practice in order to better support student learning can feel like a personal attack. Rather than hearing, “that teaching practice you’re using is less effective,” the intertwingling of teaching practices with personal identity can lead faculty to hear ‘you are less effective.’ As Smith and Herckis (2018) explain,

If advice about how to teach conflicts with these personal feelings about good teaching, faculty are likely to reject it even if it comes from scientific studies of effective instruction and improved learning.

I, for one, spent a lot of my professional life believing that showing faculty the data was all that would be necessary. That if a preponderance of well-designed studies showed that a specific teaching practice was more effective, the scholarly evidence would be sufficiently persuasive on its own. As you may imagine, I spent a lot of my professional life being disappointed in this regard. I had to hear Smith and Herckis’ message a couple of times for it to really sink in. Gorard, See, and Siddiqui (2020) provide another view:

Educators can often be skeptical about evidence, or treat it in a superficial way (Finnigan et al., 2013), depending upon their prior beliefs (Cook, 2015). So, even high quality research will make no difference unless potential users are receptive to new knowledge.

The question becomes – what can we do to help faculty be more receptive to new knowledge about evidence-based teaching practices? What would be the first steps of a professional development experience with a high likelihood of helping faculty make long-lasting changes to their teaching practices that will benefit student learning?

Perhaps it begins with helping faculty understand – both intellectually and emotionally – that they are not their teaching practices. If we can help faculty create some intellectual and emotional distance between themselves and their current approach to teaching, that space can become a place of new possibilities.

The post Intellectual and Emotional Obstacles to Adopting Evidence-based Teaching Practices first appeared on Lumen Learning.]]>Chapter 13

Dr. David Wiley, Co-Founder, Chief Academic Officer

This chapter reviews Bloom’s classic 1984 article on the “2 sigma problem.” Personally, I find this article to be one of the most inspiring pieces of writing on education of all time. The article isn’t inspirational in a way that pithily rejects the education establishment while holding up a supposedly superior model, like the misquoted and misattributed “education isn’t the filling of a pail, but the lighting of a fire.” Rather, this article demonstrates, through a rigorous, randomized experiment, that the “average” student has incredible academic potential.

In the study, students were randomly assigned to one of three conditions. The Conventional condition had students in a typical classroom setting, with one teacher and 25 – 30 students. The Mastery Learning condition was similar, except that students in this condition received detailed feedback on their tests and were given opportunities to retake equivalent tests in order to achieve mastery. In the Tutoring condition, students either worked one-on-one with a teacher or in a group of two to three students and one teacher. The result? The average student in the Tutoring condition performed two standard deviations better than the average student in the Conventional condition. And because standard deviations are represented with the Greek letter sigma, this result became known as the 2 sigma problem.

“But the students in the Tutoring condition did better… what’s the ‘problem’?” you might ask.

If sigmas aren’t your thing, let me put the results in different terms. The average student in the Tutoring condition performed better than 98% of students in the Conventional condition. The “2 sigma problem” is that we now know that the average student is capable of truly amazing academic performance, but that as a society we can’t afford to help them realize that potential. (We can barely afford one teacher for a classroom of thirty students. Imagine the cost of hiring a full-time tutor for every single student!) When you see that kind of potential going unrealized on a massive scale, it’s a problem.

Bloom gives this call to action in the article:

“If the research on the 2 sigma problem yields practical methods – which the average teacher or school faculty can learn in a brief period of time and use with little more cost or time than conventional instruction – it would be an educational contribution of the greatest magnitude.” (p. 6; emphasis in original)

The educational technology establishment’s response to this call has largely been to develop “intelligent tutors” in order to scale tutoring to all students. Since teachers are the expensive part of the equation, the logic goes, the obvious answer is to replace them with software.

At Lumen, we reject this dehumanizing interpretation of Bloom’s call to action. Our approach is to recognize that, as Bloom wrote elsewhere, different students need different amounts of help. Some students will earn As with no tutoring at all. And those students that do need help sometimes don’t need it all the time. Based on this realization, Lumen’s courseware makes it easy for faculty to (1) see which students need help, (2) see which specific topics they need help on, and (3) invite them to come to office hours (or another individual or small group setting) to get the help they need. We hypothesize that this approach can both scale to meet the needs of all learners and honor and value faculty-student relationships.

Reading Research on Learning Part 1: What You Know Determines What You Learn

About This Series

At Lumen, everything we do is focused on improving student learning. You already know that we create awesome and affordable interactive courseware, engage in both data-driven and community-driven continuous improvement, and support faculty professional development. You might not know that we also do things like our “Not a Book Club,” in which the whole company is invited to engage with the research on learning.

We recently finished How Learning Happens: Seminal Works in Educational Psychology and What They Mean in Practice by Kirschner and Hendrick (2020). This is a terrific and really accessible book that summarizes and explains some of the most important research about how we learn. We had a great time discussing the book’s chapters (there’s one chapter for each research article) and talking about how that research shows up in our courseware and professional development designs. I thought it would be fun to share some of those insights with you in a brief series discussing several of the book’s chapters, so here we go.

The post Reading Research on Learning: In Pursuit of the Holy Grail first appeared on Lumen Learning.]]>Chapter 6

Dr. David Wiley, Co-Founder, Chief Academic Officer

This chapter is about Ausbel’s 1960 paper on “advance organizers” (and no, it’s not “advanced organizers”). The key insight of this paper is that “the single most important factor influencing learning is what the learner already knows.” Or, as Kirschner and Hendrick write, “In plain English, [Ausubel] holds that learning is a process in which new, to-be-learnt information is related by learners to what is already present in their existing cognitive structures…. learning and retention are facilitated when the learner has acquired a meaningful cognitive framework that allows new information to be organized, assimilated, and subsumed in what is already known” (p. 57).

To oversimplify it just a bit, imagine a hat rack, where each hook represents something the learner already knows. Each time a teacher (or an instructional designer) introduces a new idea, concept, principle, or process, part of their job is to help learners identify a hook to hang this new hat on. Explicitly helping learners understand how new information relates to things they already know gives them a framework for interpreting and understanding.

Advance organizers are a way of “activating prior knowledge,” as we say in the instructional design business. They’re brief descriptions, stories, or graphics that get students thinking about the relevant things they already know, and help them prepare to connect the new things they’re about to learn to those things they already know.

In Lumen’s Waymaker and OHM courseware, we dedicate the first section in each module – titled “Why It Matters” – to this task of activating prior knowledge and helping students prepare to integrate new information with what they already know. (We also provide additional support for that integration in the final section of each module, which we call Putting It Together.)

What are you reading about learning? How are you using it to better support your students’ learning?

About This Series

At Lumen, everything we do is focused on improving student learning. You already know that we create awesome and affordable interactive courseware, engage in both data-driven and community-driven continuous improvement, and support faculty professional development. You might not know that we also do things like our “Not a Book Club,” in which the whole company is invited to engage with the research on learning.

We recently finished How Learning Happens: Seminal Works in Educational Psychology and What They Mean in Practice by Kirschner and Hendrick (2020). This is a terrific and really accessible book that summarizes and explains some of the most important research about how we learn. We had a great time discussing the book’s chapters (there’s one chapter for each research article) and talking about how that research shows up in our courseware and professional development designs. I thought it would be fun to share some of those insights with you in a brief series discussing several of the book’s chapters, so here we go.

The post Reading Research on Learning: What You Know Determines What You Learn first appeared on Lumen Learning.]]>In January of 2020, we started an experimental community-driven continuous improvement project with a few of our Waymaker courses. This was the continuous improvement process we followed:

- We added a “Contribute!” button to the bottom of every content page.

- The “Contribute!” button sent users to a Google Document version of the page with comment and suggestion privileges turned on.

- Any student or teacher had the ability to write comments or suggestions in-context on the page.

- We monitored suggestions, provided timely feedback, and decided whether to include the suggestions in the course.

- If we included the suggestion in the course we would add the contributor’s name to the acknowledgments section. If not, we responded to their comment with an explanation as to why we were not taking their suggestion.

Throughout the first half of 2020, despite working through a global pandemic, we had an average of 20 community contributions per week. We were pleasantly surprised to find that the contributions came from mostly students! Students were finding small errors, areas for improvement in diversity, equity, and inclusion, or areas where they wanted more practice. The feedback we received was invaluable and allowed us to improve those courses. Due to this success, in fall 2020 we rolled out the process to all of our Waymaker courses.

During fall 2020, we received an average of 150 contributions per week across all of our Waymaker courses. Again, the majority of these were from students who found small text errors, pointed out difficult words to include in our glossaries, made suggestions to improve the diversity, equity, and inclusion of our course materials, and sometimes commented when they were having a hard time learning the material. We even saw a few students starting to collaborate in the Google Documents discussing a particular issue.

Thanks to this community-driven continuous improvement we have many students and teachers included in the acknowledgments sections of our book. Introduction to Psychology, for example, has 58 people listed in the Acknowledgments section of the course content, indicating that those individuals made a suggestion or improvement to the content that ended up being accepted.

We’re excited to continue making efforts to grow awareness and participation in our community-driven continuous improvement work. Our next initiative will be a half-day virtual summit. Anyone interested in being part of our community-driven continuous improvement work in specific courses will be invited to attend. The first half of the summit will consist of presentations and panels from expert teachers showing how they have done continuous improvement in their courses, and then everyone will get hands-on and dive right into continuous improvement, working on the learning outcomes our nationwide data shows students struggle with the most in a specific course.

Stay tuned for more details or email us at info@lumenlearning.com for more information.

The post An Update On Our Community-Driven Continuous Improvement Efforts first appeared on Lumen Learning.]]>A substantive body of research demonstrates the incredible impact teachers can have on student learning when they know where their students are in the learning process and adapt their teaching to meet their learners’ specific needs. These adaptations are most effective when grounded in relationships of care and trust between teachers and students. (We provide a high-level discussion of this research in the final section of this article.)

Lumen’s Waymaker courseware applies these principles in course materials developed using open educational resources (OER). Waymaker courses curate learning outcome-aligned text, video, practice questions, simulations, and other learning activities designed to help students master the content. They also include features specifically designed to help catalyze meaningful teacher-student relationships and to support teachers in developing accurate understandings of where their students are – while there’s still time for teachers to influence student learning.

While these features are grounded in research, that doesn’t guarantee that they’ve been designed and implemented in a way that will actually result in improved learning for students! Below, we describe our implementation of these features in Waymaker courses used by thousands of students between August 2017 and August 2019, and the results of an empirical test of its influence on student learning.

How Waymaker Supports Teacher-Student Relationships

In Waymaker’s mastery-based model, all students are given at least two opportunities to take each end-of-module quiz. This quiz is comprised of outcome-aligned items that are drawn from a pool, so that a student’s second attempt is on a quiz equivalent to their first quiz, but not the same quiz.

Waymaker’s messaging tools help faculty track how students are doing and greatly simplify the process of reaching out to struggling students for one-on-one follow up. When a student fails to achieve mastery (set by default at 80% correct) on their first end-of-module quiz attempt AND that student has made use of the practice opportunities built into the courseware, they are brought to their faculty’s attention in this dashboard:

When the faculty clicks MESSAGE in the Actions column, they see a templated message filled in with information specific to the student, including their name and the specific learning outcomes they struggled with on their first quiz attempt. The message invites students into a conversation with their faculty member, either face-to-face during office hours or synchronously in some other medium. Faculty can review the message, edit it if they choose, and then send it on to the student.

But Does It Impact Student Learning?

We examined the amount of improvement 30,678 students saw between their first and second quiz attempts over a total of 164,354 quizzes. We divided students who failed to achieve mastery on their first quiz attempt into two groups: (1) those who were sent a message like the one above by their faculty and (2) those who were not sent the message.

The graph below shows the amount of improvement each group of students saw between their first and second quiz attempts. As students’ scores on their first quiz attempt gets higher, the amount they improve on their second attempt decreases – because they have less room to improve. The size of the difference in improvements between the two groups also decreases similarly.

The difference in the amount of improvement the two groups saw from their first to their second quiz attempt is statistically significant, with students who were sent messages by their faculty improving significantly more than students who were not sent messages.

There is an interesting issue in these data which deserves further study. Some students begin their second quiz attempt immediately following their first quiz attempt. This student behavior does not allow faculty time to reach out and help them. Consequently, the faculty behavior of interest (sending messages) is inversely correlated with student behavior (not waiting between quiz attempts) which may have its own independent relationship with improvement between attempts. Additional research into this relationship is needed.

Previous Research Exploring Teacher Impact on Learning

Hattie (2015) describes lessons learned from synthesizing the findings of 1200 meta-analyses relating to influences on student achievement. (This is called a meta-meta-analysis!) These 1200 meta-analyses include more than 65,000 studies, which in turn include around a quarter of a billion students. In the summary section of the article, he writes:

The estimates from the synthesis are that about 50% of the variance in learning is a function of what the student brings to the lecture room or classroom… About 20% to 25% of the total learning variance is in the hands of teachers (p.87).

Of course the learner – who is the one doing the learning – plays the largest role in this process. But the role of the teacher can also be massive! We all know the importance of teachers intuitively, but there are a lot of things people intuitively “know” about education that are totally and completely wrong (looking at you, learning styles). So, having empirically confirmed the magnitude of the influence teachers can have on student learning, we are naturally led to ask – how can teachers maximize their influence on student learning?

On Hattie’s website there’s a running list of the 195 influences he and his team have reviewed in their meta-meta-analyses. This list is sortable by effect size (the degree of impact of the influence on student learning) and each influence is categorized by domain and subdomain. One of these groupings is “Teacher” (others are School, Student, Curricula, and Teaching). The highest impact practice in the Teacher category, and the third most impactful influence overall (third out of 195), is “Teacher estimates of achievement” (d = 1.29). This means situations in which a teacher has an accurate sense of where each learner is in their learning, and proactively uses that knowledge to decide how to adapt their teaching.

The notion of “teacher estimates of achievement” is closely related to many other high ranking influences on Hattie’s list. In this article, we focus on “Teacher – student relationships.” This is another high ranking influence within the Teacher category (d = 0.52). In 2009, Hattie wrote:

Building relations with students implies agency, efficacy, respect by the teacher for what the [learner] brings to the class (from home, culture, peers)… Developing relationships requires skills by the teacher – such as the skills of listening, empathy, caring, and having positive regard for others.

We share this quote from Hattie’s first book to demonstrate that these relationships are not simply instrumental. That is, they’re not just a way for teachers to continuously update their estimates of student achievement. As Hattie and Zierer (2019) wrote later, “The teacher-student relationship has a huge impact on student achievement. Without a foundation of trust, learning and teaching are virtually impossible” (p.101).

Hattie’s exhaustive research demonstrates the incredible influence teachers can have on student learning when teachers are aware of how their students are doing and they proactively engage those students based on that knowledge. Faculty use of Waymaker’s messaging tools, which are designed to support the development of teacher-student relationships and improve “teacher estimates of achievement,” is associated with statistically significant improvements in student learning. We’re always working to make Waymaker better, but it’s great to know we’re on the right track.

Interested in Learning More?

Digital courseware provides an exciting opportunity to try out evidence-based learning tools, assess their effectiveness, and make improvements to increase their positive impact on learning and teaching.

Visit Lumen’s website to learn more about Waymaker and the variety of ways it is designed to support effective learning. If you’d like to try out how Waymaker courses work, let us know and we’ll set you up to explore any course(s) of interest.

Over the coming months, keep an eye on Lumen’s blog, where we’ll continue sharing insights about what we’re analyzing, seeing and doing to further improve Waymaker’s influence on learning and student success.

The post Supporting Teacher-Student Relationships to Improve Student Learning first appeared on Lumen Learning.]]>The potential of the “data revolution” in teaching and learning, just as in other sectors, is to create much more timely feedback loops for tracking the effectiveness of a complex system. In a field where feedback is already well established as a vital process for both students and educators, the question is how this potential can be realized through effective human-computer systems (Buckingham Shum and McKay, 2018).

Open educational resources (OER) are educational materials whose copyright licensing grants everyone free permission to engage in the 5R activities, including making changes to the materials and sharing those updated materials with others. Consequently, everyone who wants to continuously improve OER has permission to do so. (Not so with traditionally copyrighted materials, whose licensing allows only the rightsholder to alter and improve the content.) Permission to make changes is a necessary – but not sufficient – condition for continuous improvement.

In addition to permission to make changes, improvement requires a capacity for measurement. We can say we’ve changed OER without measuring the impact of those changes, but we can only say we’ve improved OER when we have measured student outcomes and confirmed that they have actually changed for the better.

Continuous improvement of OER, then, is the iterative process of:

- Instrumenting OER for measurement,

- Measuring their effectiveness in supporting student mastery of learning outcomes,

- Identifying areas where student mastery of those learning outcomes was not effectively supported,

- Making changes to the learning design of the underperforming OER aligned to those learning outcomes, and then

- Beginning the cycle again so we can:

- Measure the impact of those changes and determine whether or not they were actually improvements (not just changes), and

- Identify additional areas that need strengthening.

Engaging in the continuous improvement of OER in this manner allows us to make OER support learning more effectively each semester.

Learning Design and Continuous Improvement

Lumen instruments OER for measurement at the individual learning outcome level. Outcome alignment is at the very core of both our learning design process and our continuous improvement process. The outcome alignment process has three parts.

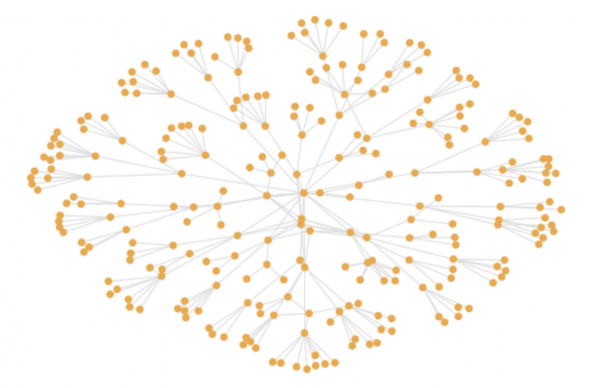

A visualization of the relationships between the more than

250 learning outcomes in Waymaker Microeconomics

First, we collaborate with faculty to identify each of the individual skills we want to support students in mastering. These detailed outcomes are, like all the content Lumen creates, licensed CC BY. Second, we align each individual page of content with the one or more outcomes whose mastery it supports. Finally, we align each assessment item with the outcome it is designed to assess. In the case of Waymaker Microeconomics, for example, that means aligning over 2,350 individual assessment items appearing in pre-tests, interactive practice opportunities, self-checks, and end of module quizzes with the appropriate learning outcome.

If that sounds like an incredible amount of work, that’s because it is!

But it’s worth it. In addition to providing benefits in the learning design process that we don’t discuss here, outcome alignment is fundamental to the continuous improvement process. With assessment items aligned to individual outcomes in pre-tests, practices, self-checks, and end-of-module quizzes, we can model learning over time, from the beginning of the module (the pre-test occurs before students see any OER) to the second attempt on the end of module quiz (after students have used and reused the OER). Similarly, because all course content is outcome-aligned, we can examine how patterns of OER usage correlate with performance on aligned assessments.

Analyzing the Effectiveness of OER

This process begins with a RISE analysis. I published the RISE framework last year with Bob Bodily and Rob Nyland, two amazing PhD students at BYU. Earlier this year I also published an open source implementation of RISE in the Journal of Open Source Software. RISE analysis divides performance on assessments into two categories, higher and lower, and usage of OER into the same two categories, higher and lower. These are matrixed to create four ways of diagnosing how OER are working in support of student learning.

| Higher Grades | High student prior knowledge, inherently easy learning outcome, highly effective content, poorly written assessment | Effective resources, effective assessment, strong outcome alignment |

| Lower Grades | Low motivation or high life distraction, too much material, technical or other difficulties accessing resources | Poorly designed resources, poorly written assessments, poor outcome alignment, difficult learning outcome |

| Lower Use of OER | Higher Use of OER |

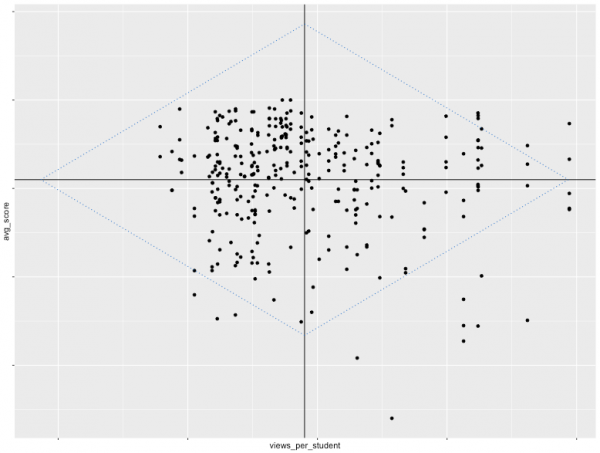

Each outcome in the course is placed in one of these four categories, as in the visualization below. We focus first on those outcomes in the lower right corner, where usage of OER is high but performance on aligned assessments is low. These are places where effort invested in improving OER is most likely to improve student learning. Below we have drawn a blue diamond three standard deviations out from the origin (mean OER usage on the x-axis and mean assessment performance on the y-axis) to make it easier to visually identify outliers in need of immediate attention.

RISE analysis visualization of Introduction to Business

Making Targeted Improvements to OER

In the past, once the OER most in need of improvement were identified, we reached out to individual faculty to invite them to participate in the process of analyzing and improving course materials in collaboration with Lumen’s learning engineers and course designers. Moving forward, we will use the Learning Challenges Leaderboards to make this information public and invite the community to participate in the process of revising, remixing, finding, or creating new OER to better support student learning.

(In addition to continuously improving the OER based on outcomes data, we also make a wide range of other updates to our courses. For example, we update OER based on faculty feedback, current events, and the availability of new OER. We make improvements to assessments based on the results of item analysis, make improvements to features of the Waymaker platform (like faculty and student nudges) based on ways they correlate with student performance, and make improvements to supplementary materials based on faculty feedback.)

The Role of Learning Materials in Education

It would be easy to look at the effort Lumen invests in improving OER and other courseware components and come to the conclusion that we think learning materials are the most important part of education. That would be a mistake. We believe deeply that the contributions made by the learner and the faculty both significantly outweigh the importance of learning materials. However, we also believe that highly effective learning materials can dramatically amplify the efforts of learners and faculty. For example, we know that highly effective learning materials can help learners reach the same levels of mastery in half the time compared to materials that follow a traditional textbook design (Lovett et al., 2008).

There are myriad ways in which education needs to be improved. The role Lumen is choosing to play in the community working to improve education (which extends far beyond problems relating to learning materials) is to enable and empower learners and faculty with highly effective learning materials that become more effective every semester.

We’re working to engage a broad community of educators and institutions in the work of improving education by continuously improving OER course materials. We’re trying to make this complex task more transparent, measurable, and participatory. Given the creativity and commitment of the community we serve, we have every hope of success.

The post A Framework for Continuous Improvement of OER first appeared on Lumen Learning.]]>Providing academic research to back up claims about cost savings attributed to open educational resources, this study documents the textbook cost to students before and after OER adoption at eight institutions in a variety of college subjects.

RESEARCH STUDY:

Cost-Savings Achieved in Two Semesters Through the Adoption of Open Educational Resources

Published in: The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning (IRRODL)

Authors: John Levi Hilton III, T. Jared Robinson, David Wiley, and J. Dale Ackerman

Publication Date: April 2014

Abstract: Textbooks represent a significant portion of the overall cost of higher education in the United States. The burden of these costs is typically shouldered by students, those who support them, and the taxpayers who fund the grants and student loans which pay for textbooks. Open educational resources (OER) provide students a way to receive high-quality learning materials at little or no cost to students. We report on the cost savings achieved by students at eight colleges when these colleges began utilizing OER in place of traditional commercial textbooks.